Looking for new ideas like searching for a needle in a haystack?

“When seeking new solutions to existing problems, criticism may hamper the ideation process. But if it’s properly applied in discovering new problems and redefining value, criticism is an engine of innovation. By finding a new direction, a company can make sense of the myriad ideas for offerings and business models and recognize the handful that will really make a difference.”

About five years ago, I came across “The Innovative Power of Criticism” in the Harvard Business Review (Jan/Feb 2016). Reading Roberto' Verganti’s excellent advice fundamentally changed how I coach people working at the earliest stages of innovation. Especially those responsible for identifying new directions, experiments, or initiatives. I refer to it so frequently, I’m posting my “Cheat Sheet” for group critique here on the blog.

There’s more detail after the six-point summary for curious readers. This has enough detail to see how you could adapt this for smaller groups/tasks. And, for readers who are looking for amusement, check out the bonus photo caption quiz at the bottom.

Harnessing Critique To Identify Promising Possibilities

Select a group of participants (include yourself).

Ask them to spend one month thinking about one or more proposals based on brand-new concepts of value.

After a month, have participants share half-baked ideas with a sparring partner.

Bring promising hypotheses to a larger group (a “radical circle”) for critique.

Converge on one or a few most promising possibilities.

Involve outsiders as necessary.

Or, click here for a basic printable version.

Editorial note: If you want to attempt this process, Verganti’s article is a must-read as my summary cuts most of the illuminating examples. In the summary below, I’ve used quotation marks to indicate direct quotes from Verganti’s (henceforth RV’s) piece. He’s super eloquent. Unless noted otherwise, emphasis in bold is mine. You’ll see this post becomes more list-like as I get deeper into the implementation, since the majority of my coaching clients like lists. (I think they are self-selecting that way. :))

The Challenge: awash in ideas, leaders struggle to identify new directions

Easy to get ideas. “Thanks to powerful ideation approaches such as design thinking and crowdsourcing, it has become incredibly easy and relatively inexpensive for companies to obtain a vast number of novel concepts, from both insiders and outsiders such as customers, designers, and scientists. Yet many organizations still struggle to identify and capture big opportunities.” In the words of one executive:

We have a mass of ideas, but honestly, we don’t know what to do with them. While we’ve tried to explore some unusual avenues, we’ve ended up committing ourselves to ideas that are already familiar.

Hard to identify valuable ones. Big changes in society fundamentally challenge conventional understanding of what is valuable. To find and exploit new opportunities, one must explicitly question existing assumptions about what is worthwhile and what is not. If organizations don’t change the lens through which they assess ideas, leaders are unlikely to identify new directions with true potential. If one is looking to innovate (which I define as novel + useful), one has two basic options:

Make incremental improvements (ideation can work well here)

strike out in new directions (often requires reinterpreting the problems worth addressing)

The Solution: Innovate Through Judgment

RV argues that “while generating lots of ideas works well for identifying improvements, it is less effective in spotting new directions….In order to find and exploit the opportunities made possible by big changes in technology or society, we need to explicitly question existing assumptions about what is good or valuable and what is not—and then, through reflection, come up with a new lens to examine innovation ideas. Such questioning and reflection characterize the art of criticism.” He goes on to say:

“Criticism” comes from the Greek word krino, which means “able to judge, value, interpret.” Criticism need not be negative; in this context it involves surfacing different perspectives, highlighting their contrasts, and synthesizing them into a bold new vision. This is a significant departure from the ideation processes of the past decade, which treat criticism as undesirable—something that stifles creativity. Whereas ideation suggests deferring judgment, the art of criticism innovates through judgment.

RV goes on to define the following “four-step process: [#s are mine]

Individuals question their assumptions and come up with new interpretations of customer problems that their company could solve.

Then people work together in pairs to refine their visions',

Before moving into a larger group for discussion.

Finally, the best ideas are tested by users and by internal and external experts in a wide range of fields.”

HMM: So how do I do that?

OMG. How to decide?

Step One: Individual reflection

If you are a leader tasked with identifying new directions, RV suggests you:

Select a group of participants (including yourself) with diverse perspectives (senior/junior; insiders/outsiders; sales/manufacturing, etc.). In his example, the manager taps 19 people, so I recommend aiming for 5-25 participants? RV emphasizes that your participation in this step is not optional.

Ask them to spend one month thinking about one or more proposals based on brand-new concepts of value. This instruction is succinct but complicated. It has three main components:

Develop individual ideas. Instead of asking people to start with customer or outsider insights, push them to start with their own. RV argues: “We all sense changes in our environment, and we all have hunches, both conscious and subconscious, about how the world might become better. We often keep these personal hypotheses private.” By pushing participants to share their ideas, intuitions could become precious raw material for creating new visions.

Reflect alone, for one month. RV says that one month “allowed people to dig deep into their own insights and not dilute or withhold them, as they might in a group brainstorming session. It gave each person freedom to perform the task as he or she saw fit—relying on a particular analytical framework, on data, or simply on intuition. This increased the likelihood that the 19 would propose diverse directions.” In addition, he points out that one month “was sufficient for each individual to sketch out thoughts, let them percolate for a few days, and then refine them and add new ones. This is especially important for coming up with provocative or outlandish hypotheses—those that are often so blurred in the early stages that they can be quickly dismissed.” I can think of many many good ideas that started out blurry.

Explicitly challenge participants to draw an arrow from the existing value proposition to the proposed one. I love this one, even though it is hard. RV’s example of a Vox executive faced when re-envisioning how furniture might better serve an aging population best illustrates of this challenge:

One person suggested that Vox think about bedrooms—the focus of only minor innovation in recent decades, but a place where elderly people spend a significant amount of time, especially when sick. He suggested transforming bedrooms from places for rest into places that contribute to health: For example, the beds might contain devices that the elderly could use to do simple exercises….Another participant envisioned a change in home furniture from being decorative and functional to being a means of socializing with relatives—for example, tables that could be easily converted into spaces for cooking, painting, or playing.

Step two: Sparring partners

Talk to one person about your idea(s).

What do you think about blue oranges?

Share half-baked ideas with a partner. After a month, once participants have initial proposals, RV says: “each person subjects his or her vision to the criticism of a trusted peer. The peer acts like a sparring partner, providing a protected environment in which the person can dare to share a wild or half-baked hypothesis without being dismissed.”

I especially like his use of the verb subjects in that sentence. Of all the steps, this one might take the most courage. Especially if you don’t know your partner in advance (in cases where you don’t have existing or obvious sparring partners, RV says you need not rely on serendipity. Rather, he recommends managers create some kind of speed-dating process whereby people with similar visions can find each other and agree to work together to polish their ideas). RV includes an excellent discussion of creative dyads, including Michael P. Farrell’s lovely definition from Collaborative Circles: Friendship Dynamics and Creative Work:

working in pairs creates an environment of “instrumental intimacy” in which people can sympathetically and constructively criticize each other.

Relative to a dyad, raising nascent or emerging ideas with larger groups or in workshops is very risky. Too often, promising directions can be dismissed, reframed or diluted before they can be sufficiently developed.

Step THREE: radical circles

Talk as a group. This is where the magic happens.

Bring promising hypotheses to a larger group for critique. In the third step, RV recommends subjecting (there’s that word again!):

…promising hypotheses to deeper criticism through discussion in a group of 10 to 20 people who have envisioned other new directions. I call this group a radical circle. Its purpose is not to decide which hypotheses are right or wrong; it is to judge why and how they are different, what important underlying insights might have been overlooked, and whether a value proposition even more formidable than all the hypotheses might be found.

To me, this is where the power of critique shines brightest, so I’m restating. Rather than decide which hypotheses are right or wrong, the radical circle judges:

why and how ideas are different.

what important underlying insights might have been overlooked

whether a value proposition even more formidable than all the hypotheses might be found.

Converge on one or a few most promising possibilities. Through discussion, the radical circle identifies the most promising directions. Like most creative work, the process must be kept positive and impersonal. RV says “Clashes should push people to dig deeper and identify more innovative spaces, not constrain thinking or compromise good ideas.” If groups find structure can assist or inform their critique (I’ve never found this to be unhelpful), RV offers a few alternatives (and of course there are countless more):

compare and contrast ideas

try to combine two ideas at a time.

create two data analytics teams; one to support the hypothesis, and one to undermine it. Then determine which is more compelling.

Step Four: Involve Outsiders

Last, RV suggests outsiders may be involved. He says:

Remember that, unlike open innovation approaches, involving outsiders is not intended to generate new ideas. Rather, it is meant to raise good questions—to challenge the innovative direction you propose in order to help you strengthen it. In addition to targeted users, outsiders should include experts from far-flung fields with novel perspectives. I call them interpreters, because of their ability to find meaning in trends that might not occur to the product’s users.

In my experience, outsiders appreciate being asked for their expertise. They appreciate that you have considered how best to use their time. Done well, these conversations can be wildly constructive and fun.

Cheat Sheet Summary: Harnessing Critique To Identify Promising Possibilities

Select a group of participants (include yourself).

Ask them to spend one month thinking about one or more proposals based on brand-new concepts of value.

After a month, have participants share half-baked ideas with a sparring partner.

Bring promising hypotheses to a larger group (a “radical circle”) for critique.

Converge on one or a few most promising possibilities.

Involve outsiders as necessary.

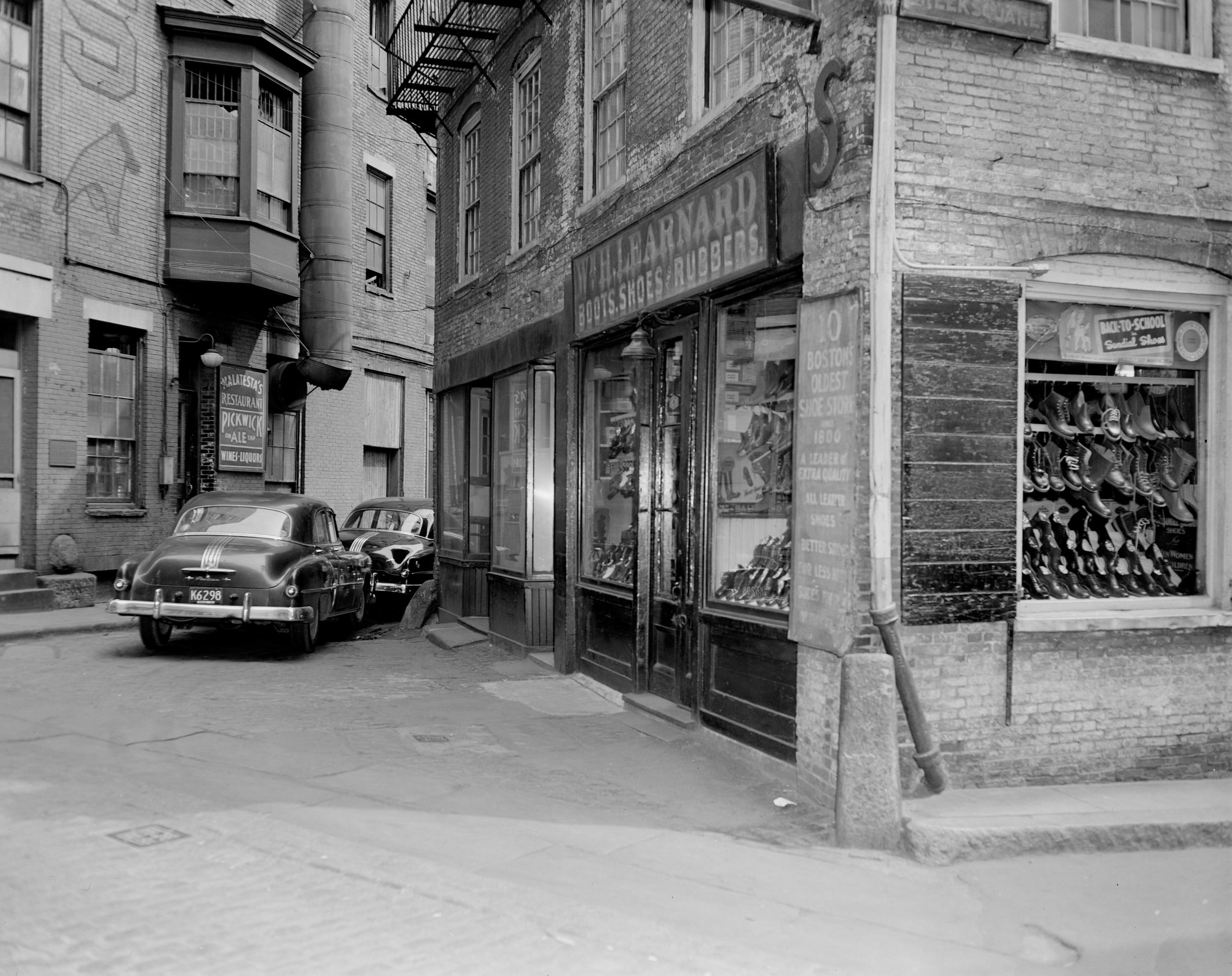

Bonus Photo Gallery

There were SO many crazy and awesome images to consider when thinking how to depict judgement. See if you can guess the captions for the six images I didn’t choose: Divergent paths? Sign posts? Forest for the trees? Dead ends? Where to start? What a mess!